Q. My income is $44,000, which is just about 341% of poverty level. I thought that subsidies were available for anyone with incomes up to 400% of poverty level, but the subsidy calculators I’ve used tell me that I don’t qualify for a subsidy. Why is this?

A. Before we get into the normal rules for this, it’s worth noting that the 400% of poverty level cap for subsidy eligibility has been removed through the end of 2022, due to the American Rescue Plan (ARP). The ARP has also increased the amount of subsidies that people can receive, even if they were already subsidy-eligible under the normal rules. So subsidies are larger and available to more people, including younger people who didn’t previously qualify for subsidies despite having an income below 400% of the poverty level. Here are some additional examples of how the new subsidy structure works.

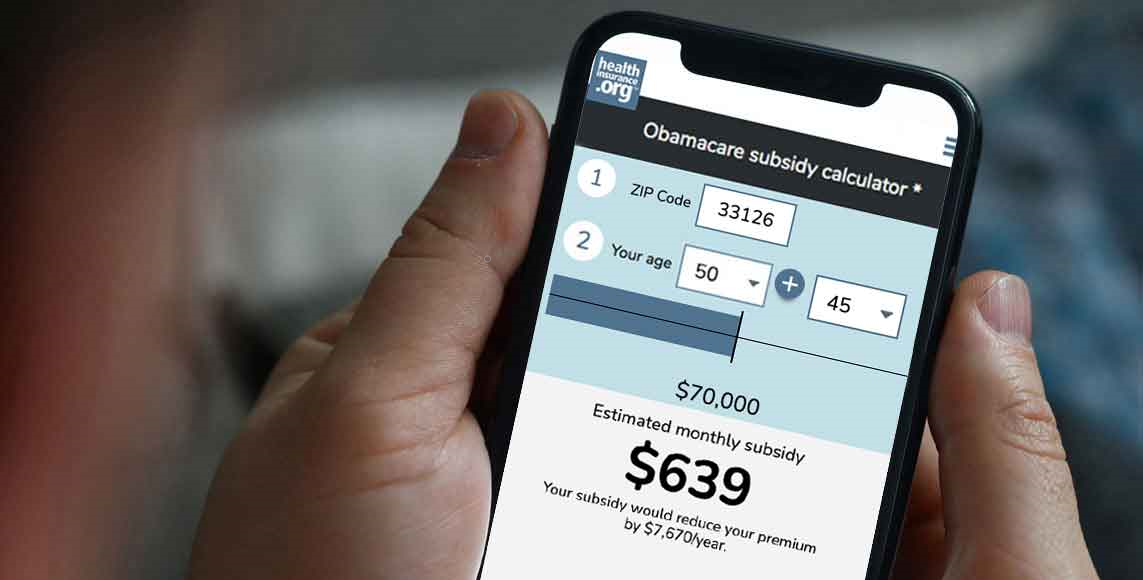

Obamacare subsidy calculator *

Unless additional legislation is enacted to extend the American Rescue Act’s subsidy provisions, the enhanced subsidies will disappear at the end of 2022 (Congress had not yet taken action to extend the ARP subsidies as of early July 2022). So we’ll show some examples here to illustrate why (especially before the American Rescue Plan) people sometimes see that they’re not subsidy-eligible despite having an income of under 400% of the poverty level.

Under normal rules (ie, without the ARP), it’s true that an income up to 400% of federal poverty level (FPL) makes you eligible for subsidies. But there’s another part of the equation: The premium of the second-lowest cost Silver plan (ie, the benchmark plan) in your exchange as a percentage of your income. If your income doesn’t exceed 400% of FPL and the premium for the second-lowest cost Silver plan in your exchange is more than a designated percentage of your income, you may qualify for a subsidy that will bring the net premium down to the percentage of your income allowed by the ACA rules (with the ARP in place for 2021 and 2022, subsidy eligibility is not capped at 400% of the poverty level; instead, people at or above that income level are subsidy-eligible if the benchmark plan would otherwise cost more than 8.5% of their income).

But if the full-price cost of the benchmark plan is already considered affordable as a percentage of your income, you won’t qualify for a subsidy. This is more likely to be the case for younger enrollees in areas where the cost of coverage is lower than average.

The ACA caps after-subsidy premiums for the second-lowest cost Silver health insurance plan (benchmark plan) at set percentages of modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), based on the percentage of FPL that the applicant’s household earns. Under the ACA, these percentages ranged from 2% to 9.5%, depending on income, and the IRS indexes them each year. For 2021, they initially ranged from 2.07% to 9.83% of income, but Section 9661 of the American Rescue Plan adjusted all of the percentages downward, resetting the amount people have to pay for the benchmark plan to a range of 0% to 8.5% of income. These numbers are being used to determine subsidy eligibility for 2021 and 2022:

- MAGI up to 150% of poverty = 0% of MAGI (ie, the subsidy is enough to make the benchmark plan premium-free)

- 150% to 200% of poverty = 0% to 2% of MAGI

- 200% to 250% of poverty = 2% to 4% of MAGI

- 250% to 300% of poverty = 4% to 6% of MAGI

- 300% to 400% of poverty = 6% to 8.5% of MAGI

- 400% of poverty or higher = 8.5% of MAGI

With an income of about 341% of FPL, if the second-lowest-cost Silver plan available to you has a premium that does not exceed about 7% of your ACA-specific MAGI in 2022, you would not qualify for a subsidy (here’s how the math works in terms of that 7%). Before the ARP changed the rules, you would not have qualified for a subsidy if the cost of the benchmark plan didn’t exceed 9.83% of your 2021 MAGI (and it would have been a similar level for 2022), so the ARP makes subsidies more widely available to people with incomes that would previously have made them subsidy-ineligible.

Premiums are based on age, so premiums for younger applicants are often low enough – with no subsidy at all – that they do not exceed the percentage of income caps on the higher end of the subsidy eligibility range. But again, the ARP has changed this in many circumstances, since it requires people to pay a smaller percentage of their income for the benchmark plan, and provides subsidies to make up the difference. This results in some young people becoming eligible for subsidies even though they didn’t previously qualify.

Subsidies fluctuate significantly from one exchange to another and even among regions within a state, since there is wide variation in the price of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan from one area to another. As you can see in this comparison sheet, a 25-year-old in Albuquerque would not have qualified for a premium subsidy in 2021 (under pre-ARP rules) with an income of $40,000. But with the ARP in place, they qualified for a subsidy of $36/month in 2021.

But because premiums are higher in other areas, that same 25-year-old earning $40,000 would already have qualified for a subsidy in Jackson, Mississippi or Cheyenne, Wyoming, but the subsidies are larger under the ARP.

Applying this to your own situation — is a subsidy necessary to make your coverage affordable?

Although the above examples apply to specific ages and areas, you can do the same calculation for any age or zip code (note that the exchange will automatically do these calculations for you).

- Go on the exchange in your state (HealthCare.gov or the state-run exchange, depending on the state) and get quotes using the browsing tool, without putting in any income information (you can get quotes without creating an account).

- Look for the second-lowest-cost silver plan. In most cases, you’ll be able to filter the results to only show silver plans, and just look for the second-lowest-cost option (in most cases, they’ll be listed in order of cost, from lowest to highest, so you can just look for the second silver plan that shows up).

- Take the cost of that plan, and multiply it by 12 to see the annual premium.

- Divide that annual premium by your annual income, and then multiply by 100 so it looks like a normal percentage (ie, if you end up with 0.0126 you’ll multiply by 100 to get 12.6 percent). That’s the percentage of your income that you’d have to pay for the benchmark silver plan without a subsidy.

- Now look at the chart above that shows the percentage of income that people in each income range have to pay for affordable coverage (if you’re in the middle of a range, you can do some math if you want to, or you can just estimate something in the middle if you’re looking for a rough idea of your subsidy eligibility).

- If the percentage of income you have to pay for the benchmark plan is above the percentage shown on the chart, you’ll get a subsidy (assuming you’re otherwise eligible — ie, you don’t have access to coverage from an employer, aren’t eligible for Medicare or Medicaid, are lawfully present in the U.S., etc.). If it’s less than the percentage shown on the chart, you won’t get a subsidy.

- Now you can run the quote again, this time putting in your income. It will show you a subsidy if you’re eligible for one, but now you’ll understand why the subsidy applies — or, if you don’t get a subsidy, why not.

Although individual market premiums have been fairly stable since 2019, they grew substantially from 2016 through 2018 in most areas. This means it’s less common than it used to be for people under 400% of the poverty level to be ineligible for subsidies. Because overall prices are higher than they were in the early days of ACA-compliant plans, many people who didn’t qualify for subsidies in prior years will find that they do qualify now, since the subsidies are designed to keep net premiums from exceeding a set threshold — and that’s especially true for 2021 and 2022, due to the ARP.

But subsidies vary considerably from one year to the next, depending on how benchmark plan prices change in a given area. Price reductions — driven by reinsurance in many areas in recent years — will drive premium subsidies down, sometimes resulting in higher after-subsidy premiums for people in areas where overall rates have declined.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.