EDITOR'S NOTE: Healthinsurance.org's Curbside Consult is a periodic informal dialogue with medical and health policy experts about pressing issues of the day.

For this edition, I Skyped with Dr. Jonathan Gruber, who is the Ford Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and director of the health care program at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He is also the most famous health economist in the United States. He has won numerous awards, and written countless papers and academic articles. He has even written a graphic novel about health reform.

Gruber was a key designer and analyst of the Massachusetts' health reform that came to be known as Romneycare. He later performed some of the same analyses for the Affordable Care Act.

Gruber was a key designer and analyst of the Massachusetts' health reform that came to be known as Romneycare. He later performed some of the same analyses for the Affordable Care Act.

We chatted last week on Skype about the current status of health reform. It was a pretty upbeat conversation, coming in the wake of the Obama administration’s announcement that more than 7 million Americans have signed up for private coverage on the new marketplaces. We talked about the future of Medicaid, strategies to expand primary care access, lessons from the botched rollout of HealthCare.gov, and why he supports the controversial "Cadillac tax" on insurance benefits.

I hope you enjoy the conversation.

Transcript of this interview:

Harold: Welcome to Curbside Consult. I'm Harold Pollack at healthinsurance.org and with me I have the great Jonathan Gruber, one of the nation's leading health reform experts and reputed to be the architect of both RomneyCare and Obamacare among other things. By the way, that's quite a backdrop you have there, Jon, really.

Jon: Yeah. It drives my wife crazy that I do these Skype things in front of my messy office shelves.

Harold: Actually, what you should really do is turn around and pull and reveal that it is actually a poster and ...

Jon: [laughs] Poster of the messy professor.

Reports of ACA demise 'exaggerated'

Harold: So how are you feeling about the Affordable Care Act today?

Jon: Feeling pretty good. I mean, I think that certainly reports of its demise are greatly exaggerated as Mark Twain would say and it is looking as good as we could hope at this point. But the bottom line is it's still too early to know for sure. We know it hasn't failed. We know that we have enough people, so it's working, but we don't know really the two critical things. One is, we don't know how many people have actually gained insurance coverage, and we also don't know really enough about the health mix of whose in and what's going to happen to premiums.

Harold: So when will we get some information about that last point?

Jon: The information is going to start to come out this summer. What we have to be careful about, it's going to come out in dribs and drabs. In particular, the states where the numbers are bad might release them first because the states that oppose Obamacare might run to release their rates saying, "look how much rates went up."

I think we have to be very careful to wait till the rates are in from everywhere, including places where Obamacare went well like California, and then look at aggregate effect and I think the relevant benchmark is 10 percent. Doing some research now, which will be out in a few weeks from the Commonwealth Fund, which shows that if you look at the rate filings in the individual insurance market in the pre-ACA period, the average annual rate of growth was 10 to 11 percent in the individual market. So that should be our benchmark.

I don't think, given how early we are in the cost control efforts of the ACA, I don't think we should be that locked into beating it, but I think if we do, if we come in, in single digits, that's a big win. If we come in 20 percent plus, that's a problem. I think we are just going to have to see what comes in relative to 10 or 11 percent it was going up beforehand.

Harold: One thing I like about that, what you're just saying is, with all the political polarization, it's nice to have a couple of numbers that are basically hard to fudge that would give us some genuine market signal about how at least insurers perceive it's going.

Jon: Exactly. I think the enrollment number was never ... the 7 million – the elusive 7 million – that was just a CBO projection. That was never a normative guide to anything. It got a life of its own – partly the administration's fault and partly, I'm a bit disappointed with the tally of 7 million, because once again we are giving the CBO numbers a life of their own, when really they can just be saying, look, the exchanges are working; that's what matters. The first hard numbers we'll get that matter will be rates and those will start dribbling out this summer.

Improved online experience

Harold: Are there certain website problems basically behind this at this point?

Jon: At the national level, yes. Not in a number of states including my own state Massachusetts website problems remain, but the national website ... Actually, it's amazing how quickly they fixed it. It really was about a six-week problem and really by mid November, things were working pretty well. Actually, it's well behind us at this point.

Harold: Do you think there were any lessons for future public enterprises of this sort from the difficulty in rolling out this website?

Jon: I think there is. I think I've lived through this in Massachusetts. I'm on the Connector board here, so I've seen our own snafus. I think the lesson is that when you have a major government project like this, you tend to have too many folks trying to run it. And there needs to be one point person who has the final say, who reports directly to the president – or in our case, directly to the governor – who has the absolute final say over everything.

In Massachusetts, and I think in the federal government, they had too many different people giving orders and that led to a lot of the problems. I think the other lesson is that you need to sort of be modularly testing. My understanding, the federal government that we see in Massachusetts, is this promise of these big deliveries and then you are waiting, waiting, it doesn't come and all of a sudden, you've got nothing. We need to sort of focus on smaller, more modular deliveries along the way.

Harold: I must say that I feel as culpable as anyone for not anticipating some of the problem – not that I had any influence over anything – but a lot of people like me who were very focused on the policy disputes, really were not necessarily focused on the nuts and bolts public management of doing the thing.

Jon: Yeah. I actually got into some trouble here in Massachusetts because when we found out that our website was a real disaster, I sent an email – sort of a mea culpa email – around to the board members saying, "Look, you know, we sort of messed this up, and part of the reason we messed this up – not totally ... we were a very small part of the problem ... but part of the reason we didn't catch it is because we all like working on the policy stuff." That's more fun, and basically the exchange had worked so well in Massachusetts for so many years, we kind of figured it would just run on its own, and we were just focused on the policy issues. So I think a lot of us made that mistake of not realizing how important the IT was.

Harold: We are here at Curbside Consult at healthinsurance.org and I am talking with MIT economist Jonathan Gruber. By the way, now you have a new professorship, I see. By the way, congratulations.

Jon: I'm the Ford professor. When I got it, my mom said, "Oh my God, that's not Rob Ford, is it?"

Insured vs uninsured

Harold: Yeah. You two, you guys actually have a lot of similarities. There's no doubt about it.

You mentioned that we don't really know how many people who were actually uninsured would've now been covered. It seems to me that a lot of the public conversation about this is a little screwy in terms of the way I was trained. Because first of all, a lot of the conversation concerns people on the exchange who are uninsured. And there were a bunch of people who came into the Medicaid program who are uninsured who tend to be ignored.

But also, that if we think of health insurance as a sort of dynamic process where you move from, "I'm covered because I have a job and then I lose my job and I might become uninsured." ... You could imagine we could, almost everyone in the exchange could be coming from previous insurance coverage, but because we are preventing them from becoming uninsured, that over time, we would actually erode the number of uninsured quite substantially, even if at any given moment in time, it doesn't look like we are reaching that many of the uninsured.

Jon: That's exactly right, Harold. I think that's why in some sense to know what affect there is on the uninsured, we can't go by these surveys of guys in exchange. We've gotta actually wait till the next population survey of the uninsured comes out, and make the apples-to-apples comparison of this sort of point. We have a point in time measure of the uninsured before the ACA. We have a point in time measure of the uninsured after. That's going to be very different than what we are seeing from these surveys about who is uninsured who came in the exchange for the reason you say. Also, because insurance is so dynamic.

I just published an editorial in TPM with John Gervais. We went to the numbers on turnover in a typical year. About 7 million people lose health insurance, or last year, I'm sorry, about 7 million people lost health insurance in 2012. Seven million people lost health insurance; 3.6 million of them were because they lost jobs and lost their health insurance. So that's 3.6 million people that year who, over the course of the year, would be coming to the pool of the uninsured. That's not accounted for in these numbers. So I think it's really just too early to say.

Harold: I was trying to explain to reporters that if they just understood that health insurance is a continuous-time Markov chain, it would all basically be very straightforward.

Jon: I'm sure that goes over really well.

The importance of the 7 million

Harold: It did go over really well. I also made a lot of jokes about data versus datums in the same conversation. It went well. Do you think that, as you mentioned, the 7 million number is not particularly a key number in the fundamental issues around health reform, but it is an accomplishment to have hit it and it's one that many people didn't think that the administration would be able to hit. Do you think that this will change the politics of ACA in a meaningful way?

Jon: I think 7 million was important as a political number, not as a substantive number, and I hope it ... I don't know if it will change the politics. I mean basically, I think everyone who was opposed will remain opposed, everyone who is for will remain for, but hopefully it will tamp down the abate a little bit. Basically, it's reminiscent of the people who were saying Romney is going to win for sure when the data clearly showed that he was going to lose. I mean, these un-skewing folks.

Basically, the question is, will folks start to admit, you're starting to hear people on the right saying, "Look, we've got to admit this is the law of the land and we've got to fix it."

I think that's great. That conversation – I'm all for talking about sort of bipartisan efforts to improve this law. I've no problem with that, but we've got to start with accepting it's the law and hopefully, hitting these kind of benchmarks will move us closer to that.

Harold: It seems so far the only real bipartisanship is between the Obama administration and some Republican governors and Washington has really no bipartisanship that's operational at the moment.

Jon: I think you're right. I think you're right.

Harold: I think that's because these governors just have responsibilities for hundreds or thousands of people, and if I'm a typical representative in the House, I'm not responsible for anything in any meaningful way.

One tragedy deserves attention

Jon: I think, Harold, the single thing we probably need to keep the most focus on is the tragedy of the lack of Medicaid expansions. I know you've written about this. You know about this, but I think we cannot talk enough about the absolute tragedy that's taken place. Really, a life-costing tragedy has taken place in America as a result of that Supreme Court decision. You know, half the states in America are denying their poorest citizens health insurance paid for by the federal government.

So to my mind, I'm offended on two levels here. I'm offended because I believe we can help poor people get health insurance, but I'm almost more offended there's a principle of political economy that basically, if you'd told me, when the Supreme Court decision came down, I said, "It's not a big deal. What state would turn down free money from the federal government to cover their poorest citizens?" The fact that half the states are is such a massive rejection of any sensible model of political economy, it's sort of offensive to me as an academic. And I think it's nothing short of political malpractice that we are seeing in these states and we've got to emphasize that.

Harold: One of the things that's really striking to me is there's a politics of impunity towards poor people, particularly non-white poor people that is almost a feature rather than a bug in the internal politics in some of these states, not to cover people under Medicaid, even if it's financially very advantageous to do so. I think there's a really important principle to defeat this politically, not just because Medicaid is important for people, but because it's such a toxic political perspective that has to be ... It has to be shown that that approach to politics doesn't work because otherwise, we will really be stuck with some very unjust policies that will be pursued with complete impunity in some of these places.

Jon: That's a great way to put it. There's larger principles at stake here. When these states are turning – not just turning down covering the poor people – but turning down the federal stimulus that would come with that.

Harold: Yeah.

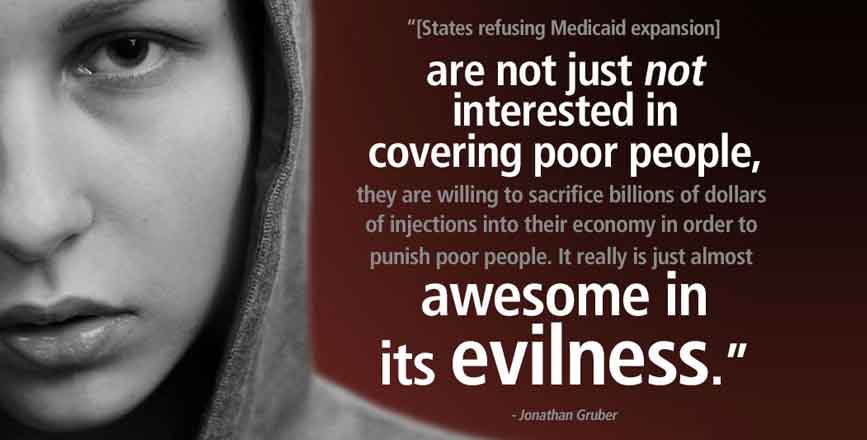

Jon: So the price they are willing ... They are not just not interested in covering poor people, they are willing to sacrifice billions of dollars of injections into their economy in order to punish poor people. It really is just almost awesome in its evilness.

Harold: Yeah.

Jon: I agree there, we have to recognize there are larger principles at stake here.

Harold: By the way, one of the real ironies is an awful lot of the institutions that would get the checks from Medicaid are in the public sector. There are also every city and county and correctional system and public hospital desperately wants this.

Jon: Yeah.

Harold: From Texas, Harris County and the City of Houston, they desperately need that money. Maybe what becomes a political forcing event will be some public hospital going out of business or something like that that really, that forces them to think differently, or maybe that just we have to wait until President Obama leaves office because it's the centerpiece of his presidency and it's just too hard to do while he's sitting in that chair.

Jon: Harold, if we look at the original expansion of Medicaid, it took about five years to get all the states in. Really, we're sort of proceeding at a similar pace. For the first few years, they didn't even have half the states. So I think we don't have to panic at this point. History does suggest that we can overcome this, but it's just very sad along the way.

Watch Part 2 of this three-part interview.

Harold Pollack is the Helen Ross Professor at the School of Social Service Administration. He is also Co-Director of The University of Chicago Crime Lab. He has published widely at the interface between poverty policy and public health. Pollack serves as a Fellow at the MacLean Center for Clinical Ethics at the University of Chicago, and as an Adjunct Fellow at the Century Foundation.