EDITOR'S NOTE:

Healthinsurance.org Curbside Consult is a periodic informal dialogue with medical and health policy experts about pressing issues of the day.

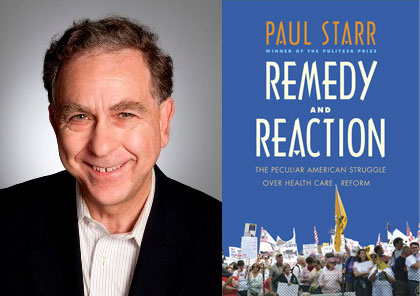

In this edition, I conversed with Princeton sociologist Paul Starr, one of America's most distinguished scholars of health policy. His 1982 classic, The Social Transformation of American Medicine won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction and many other scholarly awards. By an odd coincidence, Starr wrote Social Transformation in the very office where I completed my own dissertation, which was greeted with somewhat less renown around the world.

In the early 1990s, Starr was an inside player in President Clinton's effort to achieve universal coverage. More recently, Starr has been an acerbic ally and critic of President Obama's efforts. Starr's 2011 book, Remedy and Reaction, may be the best single history of health reform. I caught up with him November 20 for a short but sobering post-election email chat.

Pollack: Your most recent book Remedy and Reaction, describes the daunting obstacles any health reform proposal must surmount in our political process. Given the many ways health reforms can fail, politically, were you surprised that the Affordable Care Act actually passed?

Starr: Given the polarized state of our politics and the dysfunctional features of Congress, it is a surprise when any legislation passes.

Why Obama succeeded and Clinton didn't

Pollack: Why do you think President Obama succeeded, where equally skilled and committed Clinton administration failed?

Starr: There are two main differences. The first is that Democrats learned from the failure of the Clinton plan and adjusted their strategy accordingly. The second is that Obama benefited from a reform consensus that had emerged in the years leading up to 2009 and that included major interest groups and Democratic congressional leaders.

The Clinton plan was far more ambitious than the Affordable Care Act, particularly on cost containment. It included a system for global budgeting. Nearly all health insurance for people younger than 65 was to be offered through state insurance exchanges (then called regional health alliances). There were also limits on the rate of growth of average premiums in the exchange. ACA sets up exchanges only for the individual and some of the small-group market. There are no limits on premiums and no other means of imposing cost controls. So the ACA was less threatening to the health-care industry.

In 1993, Democrats were all over the place, and President Clinton was unable to overcome those divisions. By 2009, Democrats had coalesced behind the Massachusetts strategy – expanding Medicaid, subsidizing private coverage in limited insurance exchanges, and backing it up with a (weak) individual mandate. With a more unified Democratic Party and interest-group support, Obama was able to succeed in getting legislation adopted. Whether that legislation will really succeed is another matter.

Challenges ahead

Pollack: I assume you are relieved by the election. But I take it that you are pretty concerned moving forward. What do you see as the two or three biggest challenges between now and 2014, when the exchanges officially are slated to kick in?

Starr: The biggest challenges before 2014? In the fall of 2013, open enrollment is supposed to begin for the insurance exchanges. Yet according to Ron Pollack of Families USA, a recent poll by Celinda Lake showed that 78 percent of the uninsured are unaware of the new opportunities for coverage under the law.

Moreover, the legislation did not provide any funds for public education, and the 30 or so state governments controlled by Republicans aren't going to spend money to educate the public about the exchanges. So there is a significant possibility that the number of people insured through the exchanges will fall substantially short of projections.

In addition, it's not clear yet whether the federal government will have the capacity to launch a federal exchange successfully. It would be one thing if a federal exchange had been planned from the beginning; it's a different matter when states decide to leave it to the federal government with less than a year before open enrollment, and without a specific appropriation for a federal exchange. How this is going to work is at least unclear.

And then there's the likelihood that many states will not carry out the Medicaid expansion, at least not to start with.

Medicaid as a bargaining tool?

Pollack: The Supreme Court gave states the option not to expand Medicaid. ACA itself gave states the choice between setting up their own exchanges or having the federal government do this. (There is a third, hybrid option of a federally assisted exchange. I'll ignore that for the moment.)

Liberal commentators tend to treat the Medicaid expansion and the exchange issues as similar. That's probably a mistake. States have a huge long-run stake in accepting the Medicaid money. Here the parallels to the original Medicaid program remain instructive. It took about seven years for states of the old Confederacy to buy in.

States have much less obvious incentive to build their own exchange. If I were a GOP governor, what incentive do I have to establish a state exchange? It seems smart politics just to hang back. Let the federal government bear the burdens and the risks. This wouldn't, itself, be such a bad thing. But it will really strain the federal government's capacity to implement numerous exchanges across (maybe) 30 states.

Starr: I agree that states have a "huge long-run stake in accepting the Medicaid money." Actually, they have a short-run stake too. The Medicaid funds represent a big infusion of money into their state economies. But ideology can trump state interests.

Some Republican governors may use the coming months to negotiate with the Obama administration over Medicaid. For example, they may say: I'll do the Medicaid expansion if you give me a waiver on x, y, and z requirements for "old" Medicaid. It will be interesting to see how the administration plays its cards. It's holding a strong hand on Medicaid. But it's holding a weak hand on the exchanges.

You're right that Republican governors may hold back on an exchange because they don't have that strong an incentive to do one early. After all, there's nothing to prevent them from letting the federal government work out the glitches and take the blame for everything that goes wrong at the beginning. Then they take it over later if they decide that's in their interest.

The price of rejecting Medicaid

Pollack: Do you believe that governors who hang back on the Medicaid expansion will pay a political price? In some cases, they might. I co-wrote an op-ed in the Miami Herald which noted the impact of reducing Medicaid on Miami-Dade's large public hospital. That op-ed attracted surprising interest. I get the sense that Florida's governor Rick Scott is nervous about rejecting so much money.

Starr: I don't know whether governors who refuse the Medicaid money will pay a political price. But their states will pay a price from the loss of that money. In particular, under the law, federal funds for hospitals receiving a "disproportionate share" of the uninsured will be cut. That's because the number of uninsured is expected to go down. A state that refuses the Medicaid money will still lose the disproportionate-share money. So some of those hospitals are going to be in dire shape.

My hope is that the hospitals and medical schools will join with organizations representing low-income communities (both urban and rural) to convince state legislators and governors to do what is clearly in the state's interest.

Pollack: I share your hope that hospitals, medical societies, and Medicaid-funded care facilities will pressure governors. I suspect some will hold out to 2016 in the hope that a Republican president would offer better terms or at least better political cover.

Starr: Here's another consideration. States will figure out how to shift costs from their own budgets to the federal government by using both the Medicaid expansion and the insurance exchanges.

In some states, the counties are paying health care costs that they could cut if the ACA were fully carried out in their states. So they may press to get the states to implement the law.

Pollack: It seems to me that the president should be pretty lenient about measures to allow states to cost-shift onto the federal government. This may be good policy, anyway, given the strains on state finances.

Was reform worth it politically?

Pollack: Let me close with a separate question. Reading Remedy and Reaction and considering the issues raised today, I worry that no president would attempt something so massive again. President Obama actually passed health reform. Yet he received limited or uncertain political benefit. He will have to spend much of his presidency defending and implementing a complex, in some ways unpopular new law.

I worry that future presidents – contemplating the next round of health reform and other issues such as climate change – will look back on Obama and Clinton's experiences to conclude: "This just isn't worth it." This seems very unhealthy for American democracy. Do you share this worry?

Starr: Health care is so large a part of the federal government that presidents cannot avoid the issue. But if the ACA fails, will another Democratic president attempt to achieve universal coverage a different way? I'm not sure.

It depends how bad things get. If the Republicans had won the election, repealed the ACA, and block-granted Medicaid under the formula that Paul Ryan favored, we'd be looking at 60-70 million uninsured. That still might happen after 2016, and it might prompt yet another effort. This battle is going to be with us a long time.

Harold Pollack is Helen Ross Professor of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. He has written about health policy for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Republic, The Huffington Post and many other publications. His essay, “Lessons from an Emergency Room Nightmare,” was selected for The Best American Medical Writing, 2009.